JavaScript Application Design using Modules and MVP Pattern

14 Jun 2014Majority of websites today use JavaScript to do more than just hide or show a button. As code complexity grows, it becomes harder to understand and maintain JavaScript code. In this example, two approaches of designing an application will be contrasted to highlight the benefits of a modular design. Although the example is a simple game application, it still demonstrates how breaking an application into loosely coupled modules makes it easy to understand, extend and maintain.

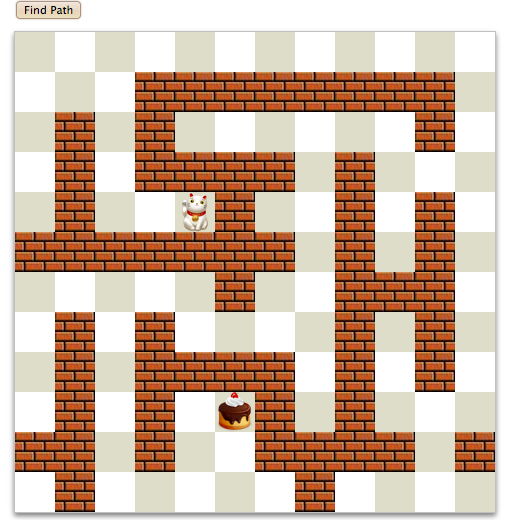

Designing a Path Finding Game

The purpose of the application is to demonstrate different path finding algorithms for a game that involves a cat looking for a cake on an interactive board. The user can draw obstacles on the board by clicking on the tiles, and move the cat or cake to set its positions. The game can then determine a path that allows the cat to find the cake when a “Find Path” button is pressed. This is how the end result may look like:

Classic Approach

Using a classic JavaScript design approach, we can do the following:

- Use divs to represent the board and the actors, which are then manipulated using jQuery

- Assign a CSS class to a div to represent various elements of the game:

- an empty square -

.square - a square with an obstacle -

.obstacle - a square with the actor cat -

.actor - a square with the goal cake -

.goal

- an empty square -

- Write a function that will query the divs using jQuery class selectors to find the positions of the cat and cake to determine the solution

In such approach, the view state and application state may get mixed together - as there are no clear separation between model and view. The setup code for the board might look like:

// generate the board layout consisting of squares

for (var row = 0; row < rows; row++) {

for (var col = 0; col < cols; col++) {

$('div.board').append('<div class="square" row="' + row + '" col="' + col + '"></div>')

}

}

// toggle between obstacle and open when a square is clicked

$('div.board').find(".square").click(function () {

$(this).toggleClass('obstacle')

})

When the game’s actor cat is dropped on a square to specify a starting position, the class attributes of the divs are updated:

// when the actor is dropped on a square

$('.square').droppable(function() {

$('.actor').removeClass('actor')

$(this).addClass('actor')

})

In this design, the code to move an actor to the square at position [10,15] may look like:

var isObstacle = $('.square[row=10][col=15]').hasClass('obstacle')

if (!isObstacle) {

$('div.actor').removeClass('actor')

$('.square[row=10][col=15]').addClass('actor')

}

Next step would be to implement the path finding algorithm. Without going any further, we can already start to notice that most of our code is entangled with jQuery. Such code may look simplistic at first, but it is hard to maintain as application logic is diffused with DOM manipulations. With time, it will become harder to follow how everything fits together - as everything is glued together with CSS selectors and callbacks. This monolithic approach makes it hard to write reusable code as most functions are littered with view specific jQuery code. If we have to change how the view is generated, we would have to change many places of the code - we may even miss a few places.

Alternative Modular Approach

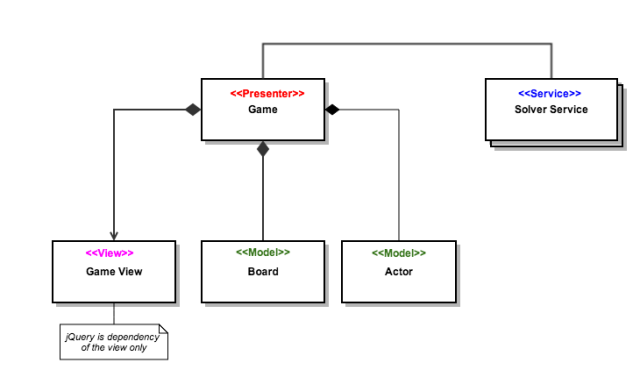

We can start by identifying clusters of functions or objects that relate closely to a single domain concept. Also, we would like to separate the concerns of displaying the board/actors from the Game so that there is a clean separation between view and business logic. Thus, we come up with:

- Board - Represents a Grid containing open tiles and obstacles

- Actor - Represents the actor of the game - the Cat

- Game - Co-ordinates the elements and rules of the game

- Game-View - Visualising the state of the game.

- Solver Service - A service or strategy to find a path from the Actor to the goal on the board. This could also be a remote service using AJAX.

We can map these cluster of functions or objects into modules. This will allow us to clearly mark the boundaries and dependencies between different parts of our application.

Identifying the specific roles of objects allow us to apply a design pattern like MVC or MVP to glue the loosely coupled parts together.

In this example, the Game object performs the role of the Presenter and the Board/Actor objects together comprise the Model. All View concerns are encapsulated in the Game-View module.

The following illustration shows the relationship between the application objects:

With such separation of concerns and single responsibility, the code to move the actor to a square will look like:

if (board.isValidMove(position)) {

actor.setPosition(position)

gameView.updateActor(position)

}

Any interaction that happens in the view is handled by the Game Presenter:

// Inside Game Presenter

// View object - Pass Presenter callbacks for event handling

var gameView = new GameView(options, {

onObstacleChange : function(isObstacle, row, col) {

board.setObstacle(isObstacle, row, col)

gameView.reset()

},

onNewStartPosition: function(row, col) {

actorPos = new Position(row, col)

gameView.reset()

},

onNewGoalPosition: function(row, col) {

goalPos = new Position(row, col)

gameView.reset()

}

})

The modular design allows us to load different Service/Strategies for solving the game - which may be loaded lazily as required:

// Solver Service returns a list of moves that leads the cat to the cake

var solution = SolverService.solve(board, actorPos, goalPos)

solution.forEach(function(position) {

game.moveActor(position)

})

In summary, the modular design allows us to create reusable components that can be easily tested and maintained. Application logic is cleanly isolated from view/DOM manipulation logic as we have moved all jQuery code into our view module. This makes the code much easier to comprehend. Since the dependencies between modules can be explicitly defined, the runtime can load modules in parallel to reduce application load time.

If you would like to play with the sample application, please find it here:

git clone https://github.com/openraz/javascript.git